Someone, probably quite rightly, has defined Parma as “the capital of Gourmets”.

Nature has in fact endowed this land with very particular and varied environmental conditions – from the sunny plain by the Po river to the green hills and the steep pinnacles of the Apennine mountains – which mankind has learned, over centuries, to exploit and refine creating typical products many of which are renowned worldwide: from the superlative Parmigiano – Reggiano cheese, to the sweet Parma Ham, to the Shoulder of San Secondo, to the wines of the hills, to the legendary Culatello, the unbeatable Porcino wild mushroom from Borgotaro to the Fragno Truffle.

Work and love of the land have made Parma, since the XIX century, the Italian Food Valley, concentrating in this area the superior quality processing of tomato, pasta, milk and various other culinary “preserves” assisted by a local mechanical industry specialized in advanced technologies for food processing.

But the mere presence of numerous typical products would not, by itself, be sufficient. Parma really has been a capital.

It was the capital city of a small Duchy cushioned between the Papal states and Lombardy, for centuries a special passage via the Apennines linking North and South Italy and Europe. On the “Via Francigena” pilgrim route, which crossed the territory, pilgrims were making their way to Rome already around the year 1000.

This natural “crossroads” has been ruled by the Farnese family of Roman descent, the Bourbons from Spain and France, and the Austrian Maria Luigia. The best dishes from the cuisines of these countries were selected at the Court of Parma, carefully revised incorporating local products and taste thus creating a rich and refined variety of delicacies.

Extraordinary gastronomy, surely, but also extraordinary history and art: in one word culture. The same “culture of taste and flavour” which the Food Museums intend to communicate to the discerning visitor, capable of savouring, slowly, this beautiful land and its delightful treasures so as to penetrate, patiently, the secrets of the “Gourmet Capital”.

FOOD AS CULTURE

an artistic tour of Parma.

Food culture is a deeply rooted part of local tradition and is captured by the artistic works of the region.

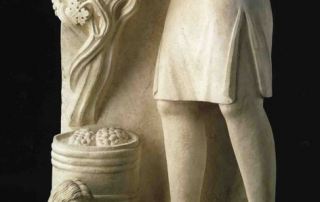

The cathedral was built in 1196 and dedicated to Maria Assunta, or the assumption of the Virgin Mary, who was immortalized by the beautiful work of Correggio in the cupola. At the main entry to the cathedral, protected by the two impressive lion sculptures, you will find the oldest depiction of someone working with pork meat.

Scenes from the months of the year are sculpted into arch over the doorway.

The anonymous sculptor from the 11th century portrayed the slaughter of a pig for the month of November.

A few feet away, you will find the rose-colored baptistery, created by Benedetto Antelami at the beginning of the gothic period.

Another cycle of the months is located inside the baptistery. The monthly scenes of men working the fields are reflected by the water in the octagonal bath basin.

There are depictions of people growing wheat, grapes and turnips.

The sign of Aquarius is represented by people making sausages and salumi inside a medieval kitchen.

Near the cathedral and baptistery, you will come across the spectacular complex of San Paolo, an ancient Benedictine monastery, built prior to 985A.D.

Inside San Paolo, you can visit the incredible apartments of the abbess Giovanna Piacenza who had the vaults frescoed by Antonio Allegri da Correggio in 1519. The iconography is a mix of figures from classic mythology and a large number of vases and table furnishings, which are usually found in depictions of in the monk’s refectory.

Further a field, beyond the large green lawn of the Piazzale della Pace, you will find the imposing Palazzo della Pilotta.

The palace was built between 1583 and 1611 by the Farnese dukes in order to host the people of the court. It is a large complex of buildings that have become the main cultural center of the city. The National Archeological Museum, the Palatina Library, the Bodoniano Museum, and the Farnese Theater are all housed here. The National Gallery and the National Fine Arts Academy are also part of the complex.

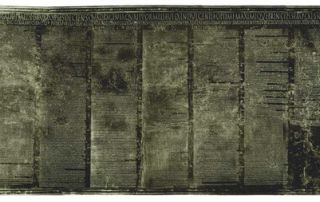

The Archeological Museum was created in 1761 by Don Filippo of Bourbon. The museum was built to preserve and exhibit the findings from the archeological digs in Roman city of Veleia. One of the highlights from the collection is the Tabula Alimentaria Traiana, the largest ancient bronze inscription. Studied by great historian Lodovico Antonio Muratori, the table contains the list of funds, and their relative owners, on loan from the Imperial bank of Trajan. The money was used for the education of the poor people in Veleia. Another interesting part of the museum is the rich collection of furnishings from around Parma having to do with the food preparation and cookery.

Also inside the Palazzo della Pilotta, there is the incredible Palatina Library, inaugurated in 1769. The library contains valuable gastronomic manuscripts, including a copy of Li quatro banchetti by the chef of Carlo Nascia, an original manuscript of Piciol lume di cucina (1701) told by Antonio Maria Dalli and written by copyist Carlo Giovanelli.

There are also printed works written by Vincenzo Agnoletti, the head cook of the Court of Marie Louise, and the original drawings for a series of dinner plates designed in 1639 for Odoardo Farnese (1612–1640) in preparation for a meal with Cardinals Antonio and Francesco Barberini from Roma. Although the lunch fell through, about one hundred designs, many of which are watercolors, reveal the esthetic of the 17th century table decoration.

The National Gallery was built to house the 17th century collections of the Fine Arts Academy of Parma and has become one of Italy’s most important museums.

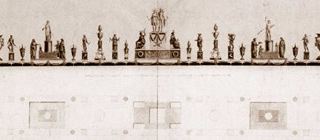

Inside the large rooms of the gallery, it is possible to view the extraordinary Trionfo da Tavola, or centerpiece, made by Spanish sculptor Damià Campaney(1771–1855). The centerpiece is made of over one hundred pieces of marble, bronze and alabaster. It was built in Rome between 1804 and 1806 to be placed in the Spanish Embassy.

Fortunately, it made its way up to Parma, after a stop in Lucca. It is a jubilant work of art that expresses how important entertaining and banquets were in the political live of the reigning European Courts of the past centuries.

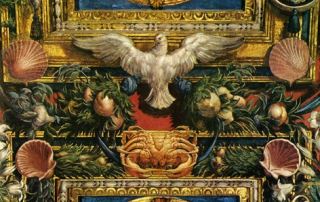

Further on, there is the Magistrale di Santa Maria della Staccata, a church containing fanciful iconography painted by the great Italian Renaissance artist Francesco Mazzola, or Parmigianino( 1503–1540).

In the arch over the main alter and the 13th century, there is an incredible collection of food-related images. There are pictures of crabs, doves, shrimp, goats, scallops and even fruit. All of the pictures have strong symbolic meaning and correspond to themes of alchemy.

Parmigianino created a lasting index of foods from the land and the sea and positioned it above the altar – the place where food was blessed for the spirit.

Piazza Garibaldi rests in the shadow of the church’s dome. The piazza was once home to the fresh food market, which was moved to the nearby Piazza della Ghiaia, many centuries ago.

Cassa di Risparmio, the local bank, (now called Cariparma – Crédit Agricole,) replaced the old market. Inside the bank building, you will find two interesting food-inspired works of art from the 20th century.

The Counselor’s Room, or Sala del Consiglio, was designed entirely – from the wall decorations to the furniture to the lighting – by Parma-born artist Amedeo Bocchi (1883–1976).

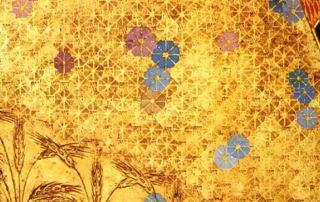

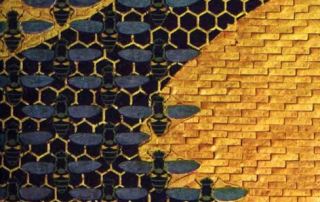

He created the room between 1915 and 1917 in a style reminiscent of Klimt and the Vienna Secession. One of the walls, dedicated to the theme of saving, symbolically depicts the work done in the fields of Parma and the abundant crops of golden wheat and honey-filled honeycombs.

Moving on, you will enter into what was once the Sala del Consiglio of the Camera di Commercio and is now the headquarters of the Istituto Bancario.

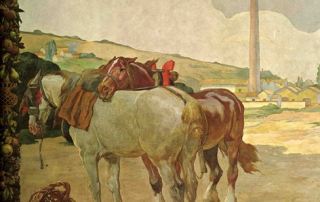

Here, you will find a room painted between 1924 and 1925 by Daniele de Strobel (1873–1942) who made large panels of oil-pained murals. The images on the walls recount how cheese was made; from the herds of cows, to the women who transported the milk, to the typical mold used for making Parmigiano Reggiano.

On the opposite wall, there are paintings of a tomato harvest and a factory for converting the tomatoes into paste and preserves.